I make a lot of reports and I’m always looking for ways to make better and more efficient reports. I recently read The Visual Display of Quantitative Information by Edward Tufte and found it illuminating. Although the book is often heavy in theory, its use of clear prose and myriad of examples – both historic and present – made me more introspective about the reports I create. Anyone who uses visuals in their work could benefit from reading Tufte’s book. In this post I’ll talk about my takeaways from the book.

On page one, Tufte lays out some ground rules about graphical displays. He believes they should:

- Show the data

- Induce the viewer to think about substance rather than about methodology, graphic design, the technology of graphic production, or something else

- Avoid distorting what the data have to say

- Present many numbers in a small space

- Make large data sets coherent

- Encourage the eye to compare difference pieces of data

- Reveal the data at several levels of detail, from a broad overview to the fine structure

- Serve a reasonably clear purpose: description, exploration, tabulation, or decoration

- Be closely integrated with the statistical and verbal descriptions of a data set

Considering that the book was published over 30 years ago, these remarks struck me as prescient. His rules may seem like a lot to take in, but if you sit back and marinate on what he’s saying, these are great guideposts.

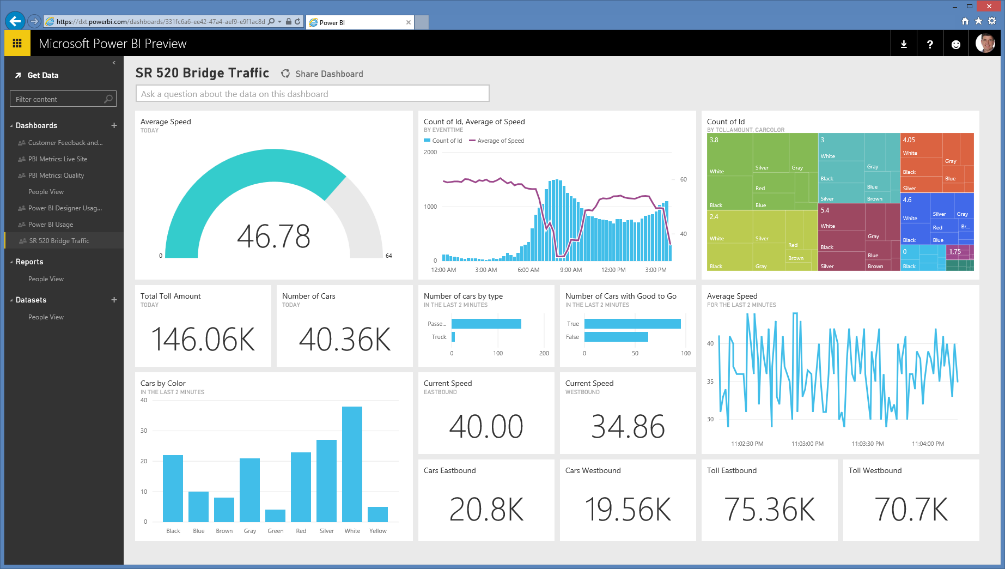

With the ubiquity of the internet and the desire to create visuals that can be rapidly shared and disseminated, accompanied with the easy accessibility of visualization tools, visualizations have been democratized and are no longer limited to academics and journalists. Today I feel that infographics and data visualizations are in what I’d call a golden age.

However, just because you can create a visual doesn’t mean it’s honest. Tufte writes that a “silly theory means a silly graphic.” I’m all about Freakonomics-style data analysis, but your approach must have a theory about the data that is grounded in reality.

Tufte believes that one of the principles of graphical excellence is a well-designed presentation of interesting data – a matter of substance, statistics, and design. Deception with visuals often may stem from visualizers believing they lack quantitative skills, or feel that graphics are only for the unsophisticated reader, and that statistical data is boring.

These shouldn’t be impediments. To create a great graphic you need to be truthful and tell the truth about the data. Truthfulness includes quoting data with the appropriate context. If comparisons and context are not provided, the visualization becomes silly.

Think of this like math class: solve this problem with a visual, but show your work. Journalists and academics I feel are pretty good at this. They often have accompanying posts dedicated to explaining how they arrived at their results and why they chose to create the graphics they did. In corporate settings however, this is often overlooked. The data may be truthful, but context is often skipped. I feel the omission is due to either time or lack of real-estate in the deliverable for said context. This struck me as something I need to be better at, and plan to incorporate into future deliverables.

One thing to note is because you may not have seen a type of graphic before, doesn’t mean it’s silly or not truthful. It is only odd because it’s new.

Speaking of silly, Tufte hates pie charts. He has a lot of vitriol for pie charts.

Tufte says, “A table is nearly always better than a dumb pie chart; the only worse design than a pie chart is several of them, for then the viewer is asked to compare quantities location in spatial disarray both within and between pies…pie charts should never be used.”

There’s a lot of pie charts out there, and they’re probably used because they’re easy. Pie charts are not attractive visuals. Tufte believes that attractive visuals contain these properties:

- Have properly chosen format and design

- Use words, numbers, and drawing together

- Reflect a balance, a proportion, a sense of relevant scale

- Display an accessible complexity of detail

- Often have a narrative quality, a story to tell about the data

- Are drawn in a professional manner

- Avoid content-free decoration, including chart junk

I can’t say every report I’m going to create is going to be full of attractive visuals; I’m bound by requirements and satisfying clients. I’m ok with that. I like telling stories with data, and from the list above, I believe that story telling is the most important property of an attractive visualization. No matter what set of visuals I am using, I need to asses that my report adheres to Tufte’s set of rules for graphical displays.

After reading Tufte’s book, I have a better idea on how to be a visualization best practices evangelist. I’ll do my best to proselytize these best practices, but I fully understand that not everyone is willing to part with pie charts.