Every day I try to be a better writer. It would probably help if I wrote every day. While emails count, I feel they don’t let me flex my writing muscle.

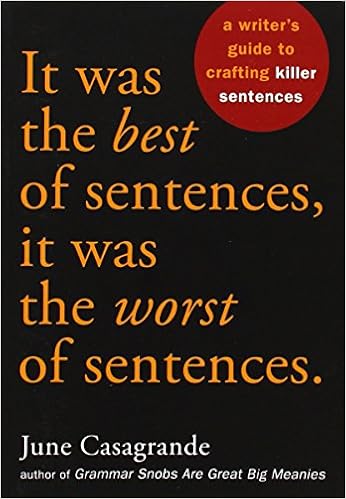

I wanted a good grammar book to read. Something that was between diagraming sentences and Strunk and White. I recently read June Casagrande’s book It Was the Best of Sentences, It Was the Worst of Sentences and found the book charming. In a breezy and conversational manner, Casagrande goes through the mechanics of good writing. I felt that for me, a busy professional, I was able to refresh my grammar without feeling beleaguered.

I found some passages to be pretty insightful, so I want to talk about them.

After going through every possible use of, Casagrande writes “you don’t need to memorize every possible job these words can do. Just begin to notice their function in a sentence and how relative clauses function in well-written sentences.”

I feel that some people leave school as grammar encyclopedias, while others don’t. I fall into the latter. It’s tough to stand up to those walking encyclopedias especially when people put you on the spot for being an English major. Reading these words was reassuring that as long as I know what relative clauses are and how they can be used, I’ll be a better writer. Rattling off their potential uses just seems to be for flash.

On the topic of adjectives, Casagrande writes “adjectives are no substitute for solid information. Often they have that less-is-more thing working against them…Divide adjectives into two categories: facts and value judgments. Adjectives that express fact can be fine, but adjectives that impose value judgements on your reader are trouble. ”

I write a lot of documentation and believe that technical writing is full of fatty prose. It’s fatty for two reasons: there needs to be context, and explaining both the why and the how. For years I wrote documentation without context. As corporate communications is starting to become more involved with the work I do (SharePoint-centric), I’ve started to add more of the why into my training materials.

I was interested to hear how Casagrande addressed fatty prose . She said fatty prose “can happen because a writer is reluctant to make a bold statement…I’m learning that it’s worth the effort to look for bold alternatives.”

She encourages writers to not know all the rules, but still be concise. I think there is some deep seated fear here which is why so many colleagues of mine dislike documentation. They fear that because they don’t know all the rules, they cannot write well. That’s some fake news right there. I personally don’t see writing as being difficult. I attest that I don’t know all the rules, but reading this book reinforced that writing is not an easy skill for most people, but you don’t need to know all the rules to be a proficient writer. Think of punk rock. Those bands often barely knew how to play their instruments yet they were concise and bold.

Back to writing, I don’t know if there’s a lot of bold alternatives when it comes to technical writing. How can I make a bold statement out of “Click Publish and your article will appear on the home page” ? I want users to understand what’s going on, but I don’t want this to be sparse like Hemingway. I believe I can make bold statements out of the non-procedural portions of the documentation. My passion is clean and concise documentation, not bold documentation. After reading this book, I want to create bold documentation. Documentation can, and should, be clean, concise, and bold. I want users to actually read this and say “Damn! That was some good documentation.”

This is the second writing book I’ve read this year, but I still don’t know all the rules. It was reassuring to read that Casagrande believes “skilled writers can defy all these principles effectively and with grace. But novice writers need to understand the concepts here. Flabby prose, repetitiveness, and statements beleaguering the obvious separate the amateurs from the pros. Make it a habit to seek out such lard in your own writing and start to look for ways in which chopping up or chopping out problem sentences can improve a whole work.”

She continues, “you’re not bound by these rules. But you are subject to expectations…don’t get entangled in these debates. Just understand the wisdom of both sides. Everyone of the writing “rules” you hear is rooted in a good idea with at least some practical application. Yet none of these rules is worth a damn when stretched into an absolute.”

The last statement really resonated with me. In this age of hyper-partisanship, we always seem to be yelling at one another. Grammar isn’t all that different. Casagrande proposes keeping our tones soft and respectful. We should reach across the grammar aisle to our draconian grammarist friends when we need to, but we don’t need to be grammar snobs to be good at writing. We need to focus on writing well first and the rest will fall into place.